Neurological disorders are conditions that affect the brain, spinal cord, or peripheral nerves, altering how signals travel throughout the body. When these signals misfire, they can disrupt the complex coordination needed for normal bladder emptying. Difficulty urinating, medically known as urinary retention or incomplete emptying, often signals an underlying problem in the nervous system.

Key Takeaways

- The bladder is controlled by both the autonomic and somatic nervous systems; damage to either can cause urinary issues.

- Multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, spinal cord injury, stroke, and multiple system atrophy are the most common neurological culprits.

- Symptoms range from a weak stream and hesitancy to complete inability to void.

- Accurate diagnosis combines neurological exams, urodynamic testing, and imaging studies.

- Treatment options include medication, pelvic floor therapy, intermittent catheterisation, and, in severe cases, neuromodulation.

Understanding the Basics

Before diving into specific disorders, it helps to grasp two core concepts:

- Neurogenic bladder - the umbrella term for bladder dysfunction caused by nerve damage. It can manifest as overactive (spastic) or underactive (flaccid) bladder.

- Detrusor muscle - the smooth muscle that contracts to push urine out. Its activity is tightly regulated by the autonomic nervous system (sympathetic and parasympathetic branches).

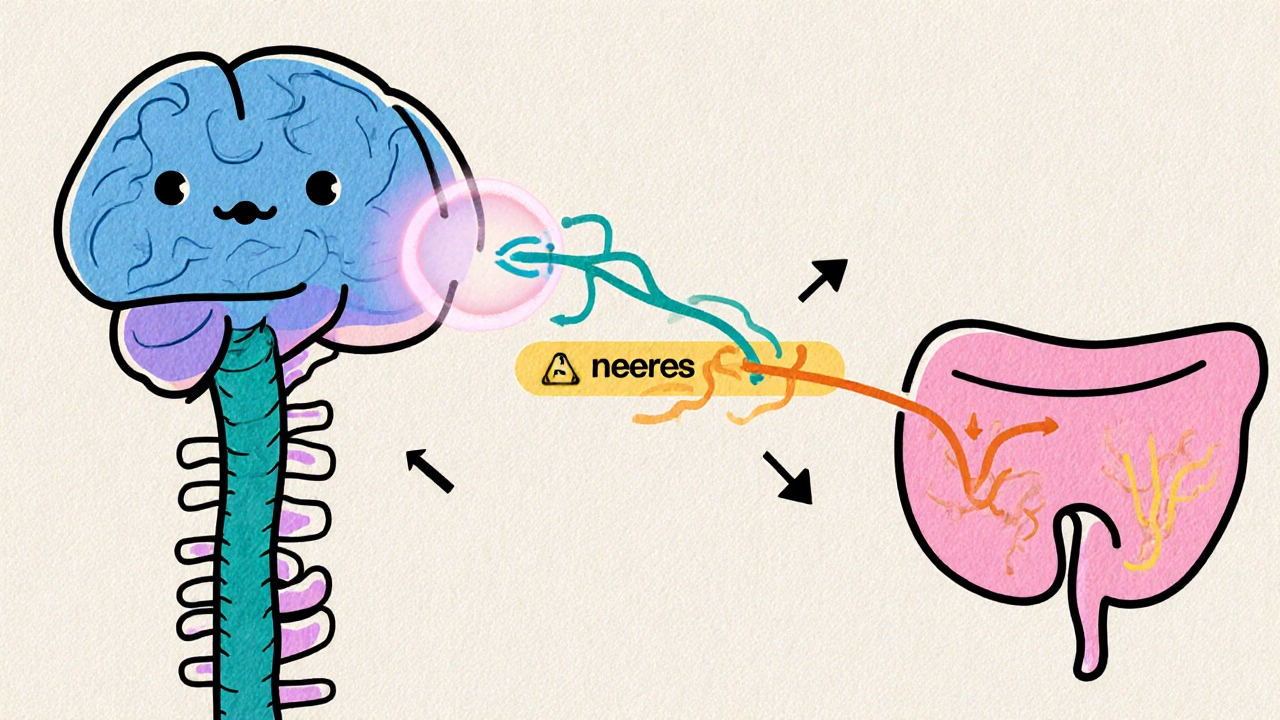

How the Nervous System Controls the Bladder

The urinary system relies on a coordinated dance between three neural pathways:

- Brain centers: The pontine micturition centre in the brainstem sends the go‑signal to empty the bladder.

- Spinal cord pathways: Descending motor fibers travel via the sacral spinal cord (S2‑S4) to the detrusor and external sphincter.

- Peripheral nerves: The pelvic nerve (parasympathetic) stimulates detrusor contraction, while the hypogastric nerve (sympathetic) relaxes it and tightens the internal sphincter.

Any interruption-whether from inflammation, demyelination, or physical injury-can throw off this timing, leading to retention, urgency, or incontinence.

Common Neurological Conditions that Affect Urination

Below are the five neurological disorders most frequently linked to urinary difficulty, each with its own mechanism.

| Disorder | Typical Urinary Issue | Underlying Mechanism | Prevalence of Urinary Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sclerosis | Urgency, frequency, incomplete emptying | Lesions in spinal cord interrupt sacral pathways | About 75% of patients |

| Parkinson's disease | Weak stream, hesitancy, nocturia | Degeneration of basal ganglia reduces coordination of sphincter relaxation | Up to 60% experience bladder dysfunction |

| Spinal Cord Injury | Complete retention or overflow incontinence | Disruption of sacral output blocks detrusor contraction | Nearly 90% develop neurogenic bladder |

| Stroke | Urgency or retention depending on lesion site | Damage to cortical control or pontine centre | 30‑50% of survivors report bladder issues |

| Multiple System Atrophy | Severe urinary retention | Degeneration of autonomic nuclei impairs sphincter relaxation | 80% develop urinary problems within 5 years |

Symptoms to Watch For

Early signs often slip under the radar because they mimic normal aging. Keep an eye on the following:

- Difficulty starting a stream or a noticeably weak flow.

- Feeling that the bladder isn’t empty after voiding (post‑void residual).

- Frequent trips to the bathroom, especially at night.

- Sudden urge that can’t be delayed (urge incontinence).

- Painful bladder emptying or a sense of pressure.

If any of these accompany a known neurological diagnosis, bring them up at your next appointment.

How Doctors Diagnose Neurogenic Urinary Problems

Diagnosis is a step‑by‑step process that blends neurological assessment with urological testing:

- History & neurological exam: Identifies lesion location and severity.

- Urinalysis: Rules out infection that could mimic retention.

- Post‑void residual measurement (ultrasound or catheter): Quantifies how much urine remains.

- Urodynamic studies: Measure bladder pressure, compliance, and sphincter activity.

- Imaging (MRI or CT): Visualises lesions affecting bladder control pathways.

These tests help clinicians decide whether the bladder is overactive, underactive, or both-a condition called mixed neurogenic bladder.

Management Strategies

There isn’t a one‑size‑fits‑all cure, but several evidence‑backed approaches can restore quality of life.

Medication

- Anticholinergics (e.g., oxybutynin) relax the detrusor to treat overactivity.

- Alpha‑blockers (e.g., tamsulosin) ease sphincter tension, useful in retention.

- Botox injections into the detrusor reduce uncontrolled contractions for refractory cases.

Catheterisation Techniques

When the bladder won’t empty on its own, intermittent clean catheterisation is the gold standard. It reduces infection risk compared with long‑term indwelling catheters.

Pelvic Floor and Physical Therapy

Specialised physiotherapists teach exercises to strengthen the external sphincter and improve coordination between bladder and pelvic floor muscles.

Neuromodulation

For patients who don’t respond to meds, sacral nerve stimulation or tibial nerve stimulation can re‑train the nervous pathways.

Lifestyle Adjustments

- Limit caffeine and alcohol-both irritate the bladder.

- Schedule regular bathroom trips (timed voiding) to prevent overflow.

- Maintain a healthy weight to reduce abdominal pressure on the bladder.

When to Seek Immediate Help

If you notice a sudden inability to urinate, severe pain in the lower abdomen, or a fever, treat it as a medical emergency. These signs can indicate a blocked urinary tract or acute infection, which require prompt antibiotics or surgical intervention.

Bottom Line

The link between neurological disorders urinary retention isn’t a mystery-damage to the nerves that tell the bladder when to contract and relax creates the problem. Recognising the symptoms early, getting the right diagnostic work‑up, and following a personalised treatment plan can keep you comfortable and avoid complications like kidney damage.

Can multiple sclerosis cause permanent bladder damage?

MS can lead to chronic neurogenic bladder, but with early treatment-medication, pelvic floor therapy, and intermittent catheterisation-most patients avoid permanent damage. Regular urodynamic monitoring helps adjust therapy before irreversible changes set in.

Why does Parkinson’s disease often cause a weak urine stream?

Parkinson’s slows the coordination between the detrusor muscle and the external sphincter. The sphincter may not relax fully, resulting in a hesitant, weak stream.

Is intermittent catheterisation painful?

When performed with proper technique and lubrication, it’s usually painless. Training with a nurse or therapist ensures comfort and reduces infection risk.

Can lifestyle changes alone fix urinary problems from a neurological disease?

Lifestyle tweaks (fluid management, timed voiding) help, but they rarely replace medical therapy when nerve pathways are damaged. They work best as part of a comprehensive plan.

What is the role of sacral nerve stimulation?

A small device sends mild electrical pulses to the sacral nerves, improving coordination between bladder contraction and sphincter relaxation. It’s effective for many with refractory neurogenic bladder.

Harry Bhullar

Understanding neurogenic bladder starts with appreciating how the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves choreograph each voiding cycle, and when any link in that chain falters, the bladder can become a reluctant partner. The pontine micturition centre normally sends a clear go‑signal, but lesions in multiple sclerosis can scramble that message, leading to urgency or incomplete emptying. In Parkinson’s disease, the basal ganglia’s loss of dopaminergic tone throws off the timing between detrusor contraction and sphincter relaxation, which explains the characteristic weak stream. Spinal cord injuries sever the sacral outflow, so the detrusor never gets the order to contract, resulting in retention or overflow incontinence. Stroke victims may have cortical damage that either hyper‑activates or suppresses bladder reflexes, depending on the lesion’s location. Multiple system atrophy directly attacks autonomic nuclei, leaving patients with severe retention that often requires catheterisation. The hierarchy of tests-urological history, post‑void residual measurements, urodynamics, and neuro‑imaging-helps clinicians pinpoint where the signal is dropping. Anticholinergics such as oxybutynin can calm an overactive detrusor, yet they won’t fix a broken sacral pathway. Alpha‑blockers like tamsulosin relax the internal sphincter, making it easier to push urine out when the nerves can’t coordinate properly. When medications fall short, intermittent clean catheterisation becomes the gold standard for safely emptying the bladder without exposing the patient to infection risk of indwelling catheters. Pelvic floor physical therapy can teach patients to harness residual sphincter control and improve coordination, especially when combined with biofeedback. For refractory cases, sacral nerve stimulation or tibial nerve stimulation re‑educates the neural circuits, offering hope for those with stubborn mixed neurogenic patterns. Lifestyle tweaks-cutting back on caffeine, scheduling timed voids, and maintaining a healthy weight-provide a supportive backdrop for any of the medical interventions. Early identification of post‑void residual volumes can prevent upper‑tract complications like hydronephrosis. Ultimately, a multidisciplinary approach that blends neurology, urology, and rehabilitation medicine gives the best chance of preserving bladder function and quality of life.