Levamisole in the Environment: A Hidden Threat?

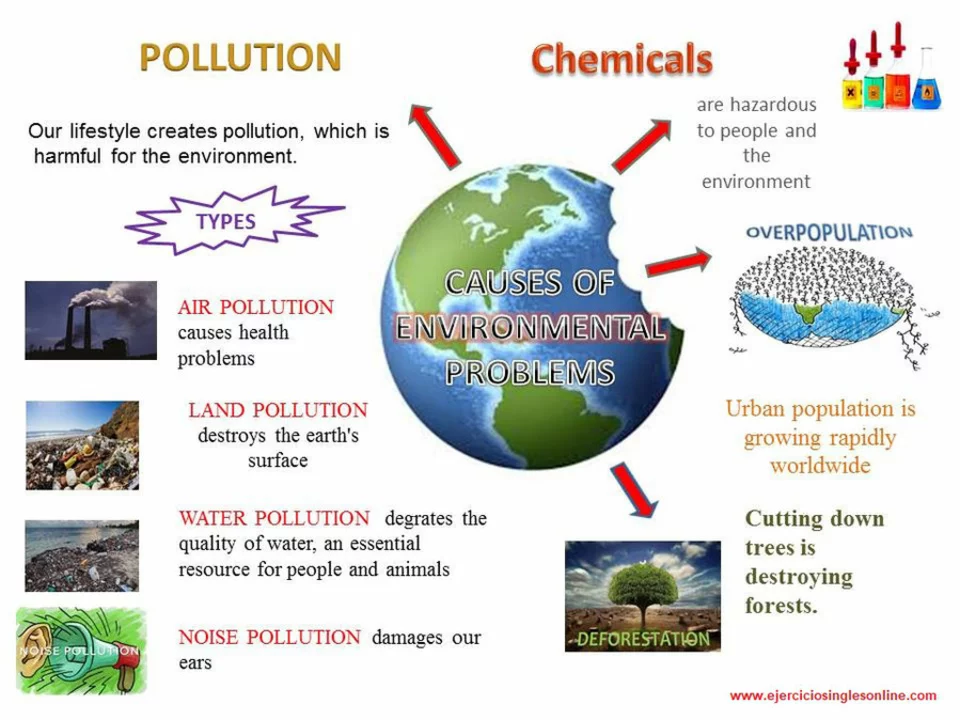

Levamisole is a widely used anthelmintic drug, which means that it is highly effective at ridding animals of parasitic worms. However, what many people don't know is that this drug can also pose a threat to the environment. In this section, we will discuss the potential ecological impacts of Levamisole and explore why this widely used drug might be considered a hidden threat to our ecosystem.

When Levamisole is administered to animals, it often ends up in their manure. This manure is then spread as fertilizer on agricultural land, where it can end up in the soil and water. As a result, Levamisole can accumulate in the environment, potentially causing harm to various species of plants, animals, and aquatic life. And while the use of Levamisole is generally considered safe for the animals that receive it, the potential for ecological harm cannot be ignored.

Effects of Levamisole on Aquatic Ecosystems

Aquatic ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of Levamisole. When this drug enters waterways through runoff from agricultural land, it can have a range of negative effects on fish and other aquatic organisms. For example, research has shown that exposure to Levamisole can cause physiological stress in fish, leading to issues with growth and reproduction.

Additionally, studies have found that Levamisole can be toxic to certain species of aquatic invertebrates, such as Daphnia magna, which are an important food source for fish. This toxicity can lead to a decrease in population size, which in turn can have a cascading effect on the entire aquatic food chain. As a result, the presence of Levamisole in aquatic ecosystems can lead to a decline in overall biodiversity, potentially disrupting the balance of these fragile environments.

Levamisole's Impact on Soil Health and Biodiversity

Soil health is crucial for maintaining the productivity and sustainability of agricultural systems. The presence of Levamisole in the soil can have a negative impact on the health and biodiversity of these systems. Studies have shown that Levamisole can be toxic to certain species of soil-dwelling invertebrates, such as earthworms and springtails. These organisms play a vital role in nutrient cycling and soil structure, so any decline in their populations can have serious implications for soil health.

Furthermore, Levamisole has been found to have a negative impact on the microbial communities within the soil. These communities are responsible for breaking down organic matter and recycling nutrients, so any disruption to their activity can have far-reaching consequences for the overall health and productivity of the soil. This can ultimately lead to a decline in crop yields and a reduction in the long-term sustainability of agricultural systems.

Are There Alternatives to Levamisole?

Given the potential ecological impacts of Levamisole, it is important to consider whether there are alternative anthelmintic drugs that could be used in its place. While several alternatives do exist, each comes with its own set of potential environmental concerns. For example, the drug ivermectin is another widely used anthelmintic, but it has also been found to be toxic to aquatic organisms and can accumulate in the environment.

However, there is some hope for the development of new, more environmentally friendly anthelmintic drugs. Researchers are currently working on the development of novel compounds that are effective at treating parasitic worms but have a reduced potential for environmental harm. These new drugs could represent a major breakthrough in the field of veterinary medicine and help to mitigate the ecological impacts associated with the use of current anthelmintic drugs, including Levamisole.

What Can We Do to Minimize the Impact of Levamisole?

While the development of new, more environmentally friendly anthelmintic drugs is an important goal, there are also steps that can be taken now to minimize the ecological impacts of Levamisole. One approach is to implement more targeted dosing strategies for animals receiving the drug. This can help to reduce the amount of Levamisole that ends up in the environment, thus lowering the risk of ecological harm.

Additionally, farmers can take steps to prevent the runoff of Levamisole-contaminated manure from their fields. This can include implementing buffer strips around waterways, which can help to filter out contaminants before they reach aquatic ecosystems. By taking these and other proactive measures, we can work to minimize the potential ecological impacts of Levamisole and protect our environment for future generations.

Nymia Jones

The deployment of Levamisole in livestock is not a benign practice; it is a calculated move by pharmaceutical conglomerates to embed persistent chemicals into our ecosystems.

By coercing farmers to spread drug‑laden manure, these corporations ensure a continuous supply of contaminants that will quietly infiltrate soil and water.

This hidden threat is deliberately obscured behind safety certifications that lack rigorous environmental scrutiny.

The public must demand transparency and stricter regulation before irreversible damage ensues.