Thyroid cancer is one of the fastest-growing cancer diagnoses in the U.S., with over 44,000 new cases each year. But here’s the surprising part: most people diagnosed with it will live for decades, often with little to no impact on their daily lives. That’s because the most common types are slow-growing, highly treatable, and respond well to targeted treatments like radioactive iodine and thyroidectomy. Still, the road to recovery isn’t simple. It involves tough decisions, unexpected side effects, and a lot of fine-tuning after treatment. This isn’t just about removing a tumor-it’s about managing your body’s balance for the rest of your life.

What Are the Main Types of Thyroid Cancer?

The thyroid gland has four main cancer types, each with different behaviors and treatment needs. The most common by far is papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), making up 70 to 80% of all cases. It usually grows slowly, often stays confined to the thyroid, and spreads to nearby lymph nodes-but even then, it’s rarely deadly. People under 45 with small PTC tumors have a 10-year survival rate above 98%.

Follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC) comes next, accounting for 10 to 15% of cases. It’s similar to PTC in prognosis but tends to spread through the bloodstream to distant organs like the lungs or bones, rather than lymph nodes. It’s less common and slightly more aggressive, but still highly treatable with surgery and radioactive iodine.

Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) is rare-only 3 to 5% of cases. It starts in the C-cells of the thyroid, which produce calcitonin, not thyroid hormone. MTC doesn’t absorb iodine, so radioactive iodine therapy doesn’t work. It can be hereditary, linked to genetic mutations like RET, which is why family screening is often recommended. Early detection through blood tests and genetic testing improves outcomes significantly.

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC) is the most feared, but also the rarest-less than 2% of cases. It grows fast, spreads quickly, and is often diagnosed at stage IV. Survival rates drop sharply: without immediate treatment, median survival is only 6 to 12 months. It doesn’t respond to radioactive iodine or standard hormone therapy. New targeted drugs like dabrafenib and trametinib have improved outcomes slightly, but it remains a serious challenge.

How Radioactive Iodine Works (and When It’s Used)

Radioactive iodine (I-131) has been used since the 1940s and remains the gold standard for treating differentiated thyroid cancers-papillary and follicular. The thyroid is the only organ in the body that absorbs iodine, so when you swallow a capsule or liquid containing I-131, the radiation goes straight to any remaining thyroid tissue or cancer cells that still take up iodine.

It’s not used for everyone. For small, low-risk papillary cancers under 1 cm with no spread, guidelines now recommend skipping RAI entirely. Studies show no survival benefit, and the side effects-dry mouth, taste changes, nausea, and long-term risk of secondary cancers-aren’t worth it. But if you’ve had a total thyroidectomy and your doctor sees high-risk features-like large tumors, lymph node spread, or cancer outside the thyroid-RAI helps wipe out any leftover cells that could come back.

Before treatment, you need to raise your TSH levels so your thyroid cells are hungry for iodine. You can do this two ways: stop taking thyroid hormone for 2 to 4 weeks (which makes you feel exhausted, cold, and depressed) or get injections of recombinant human TSH (Thyrogen®). The injections are easier but cost more. Once your TSH is high, you take the radioactive dose in a hospital or specialized center. You’ll need to isolate for a few days-no hugging kids, no sharing utensils, no sleeping next to your partner. Radiation safety rules are strict, but they’re temporary.

Modern dosing is smarter than before. The HiLo trial showed that 30 mCi works just as well as 100 mCi for low-risk patients after surgery. That means less radiation exposure, fewer side effects, and faster recovery. For advanced cases with metastases, higher doses (up to 200 mCi) are still used, but only when needed.

Thyroidectomy: What Surgery Really Involves

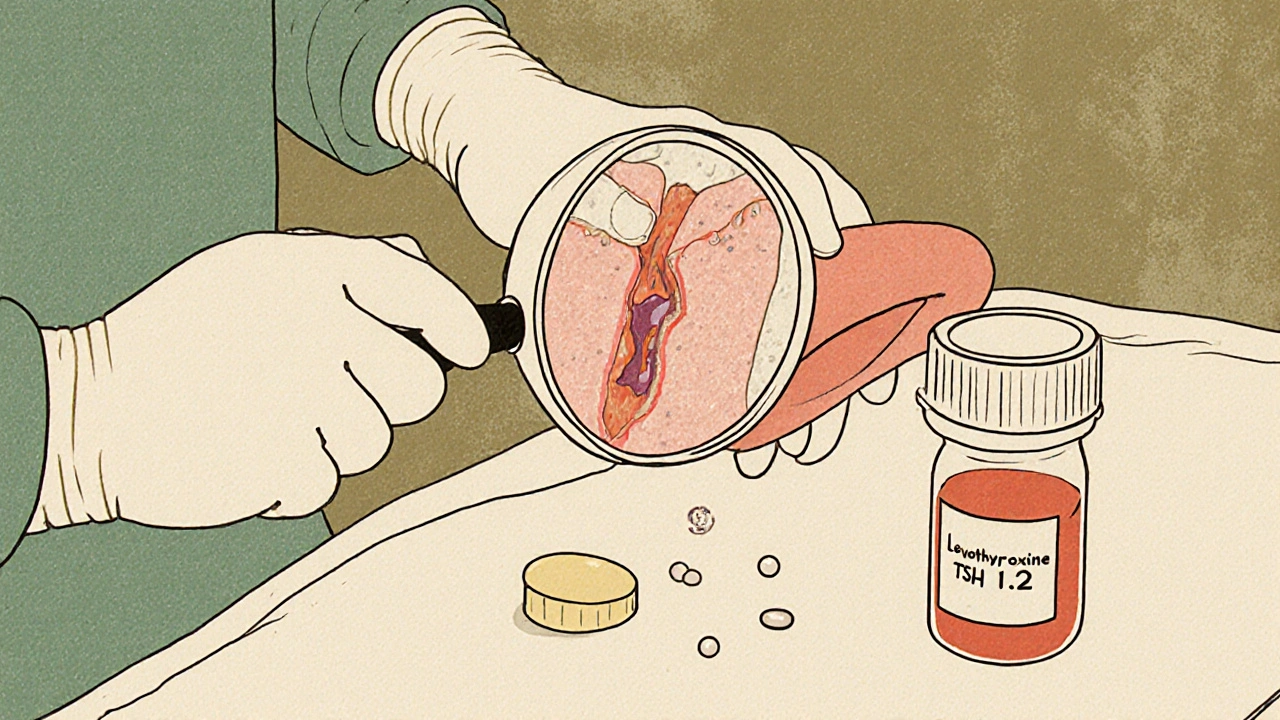

Surgery is the first step for nearly all thyroid cancer patients. The type depends on the cancer’s size, location, and risk. A lobectomy removes just one side of the thyroid. It’s common for small, low-risk tumors. Recovery is quick-often same-day discharge. But if the cancer is larger, has spread, or if there’s a genetic risk, a total thyroidectomy is needed. That means removing the entire gland.

The surgery takes 2 to 3 hours. The surgeon makes a small horizontal cut (6 to 8 cm) at the base of your neck. Modern techniques use nerve monitors to protect the recurrent laryngeal nerves-damage to these can cause hoarseness or voice loss. Surgeons also work hard to preserve the parathyroid glands, which control calcium levels. If they’re damaged or removed, you’ll need lifelong calcium and vitamin D supplements.

Complications are rare but real. About 5% of patients have temporary voice changes; 2% have permanent ones. Around 10 to 20% develop low calcium levels right after surgery, and 5% have permanent hypoparathyroidism. That means daily calcium pills, regular blood tests, and learning to recognize symptoms like tingling fingers or muscle cramps.

Minimally invasive options like transoral (through the mouth) or robotic surgery exist, but they’re not standard. Studies show higher complication rates and no better cancer outcomes. Open surgery with direct visualization still gives the best safety profile.

Life After Surgery and Radioactive Iodine

After your thyroid is gone, you’ll need to take levothyroxine every day for the rest of your life. It replaces the hormone your thyroid used to make. But here’s what most people don’t tell you: taking the pill isn’t the hard part. It’s feeling like you’re still not quite yourself.

Surveys of thyroid cancer survivors show that 68% still struggle with fatigue, brain fog, or weight gain-even when their TSH levels are “normal.” Doctors aim for a TSH between 0.5 and 2.0 mIU/L for intermediate-risk patients, but some people feel better at the lower end of that range. Finding your personal sweet spot takes time and patience.

Calcium levels matter too. After surgery, your doctor will check your blood calcium weekly at first, then monthly. Normal is 8.5 to 10.2 mg/dL. If it drops below 8.5, you’ll need supplements. Too high, and you risk kidney stones. It’s a tight balance.

Many patients report that the low-iodine diet before RAI is harder than the surgery. No bread, dairy, eggs, seafood, or iodized salt for two weeks. It’s isolating, tiring, and leaves you feeling weak. But it’s necessary. Without it, the radioactive iodine won’t work.

What’s New in Thyroid Cancer Treatment?

Thyroid cancer care is changing fast. In 2023, the AJCC updated staging to include molecular markers like BRAF and RET mutations. These help predict how aggressive a tumor is, so treatment can be tailored better. For medullary cancer with RET mutations, drugs like selpercatinib can shrink tumors and control disease for years.

For anaplastic thyroid cancer, the combo of dabrafenib and trametinib (targeting BRAF mutations) boosted median survival from 5 to over 10 months. That’s huge for a cancer that used to be a death sentence.

Researchers are now testing drugs that can “redifferentiate” cancer cells-making them absorb iodine again, even if they stopped before. Selumetinib showed promise in trials, helping over half of RAI-resistant patients regain iodine uptake. That could mean a second chance at radioactive iodine therapy.

But the biggest shift isn’t in drugs-it’s in mindset. Experts now agree that many patients are overtreated. Up to 30% of people with low-risk papillary cancer get total thyroidectomies or RAI when they don’t need them. Active surveillance-watching small tumors with regular ultrasounds-is now a valid option for some. It avoids surgery and its side effects, with only a 3.8% chance of tumor growth over 10 years.

What to Ask Your Doctor

If you’ve been diagnosed, here are five essential questions to ask:

- What type of thyroid cancer do I have, and what’s the risk level?

- Do I need a lobectomy or total thyroidectomy? Why?

- Will I need radioactive iodine? What’s the dose, and why?

- What are the chances of voice changes or low calcium after surgery?

- Can I avoid thyroid hormone withdrawal? Is Thyrogen® an option?

Don’t be afraid to ask for a second opinion. Thyroid cancer care varies widely between hospitals. A specialist in endocrine surgery will have more experience and better outcomes than a general surgeon.

Where to Find Support

Thyroid cancer survivors often feel alone-even when they’re doing well. Forums like the Thyroid Cancer Survivors’ Association and Reddit’s r/thyroidcancer are full of people sharing real stories: the sleepless nights after surgery, the frustration of brain fog, the relief when a scan comes back clear. You’re not the only one who feels this way.

And you’re not alone medically, either. With survival rates this high, thyroid cancer is becoming a chronic condition-not a death sentence. The goal isn’t just to live longer-it’s to live well.

Is thyroid cancer curable?

Yes, most types of thyroid cancer are highly curable. Papillary and follicular thyroid cancers have 10-year survival rates above 95% when caught early. Even with spread to lymph nodes, the outlook remains excellent. Medullary cancer has lower survival rates but can be controlled with surgery and targeted drugs. Anaplastic thyroid cancer is the exception-aggressive and hard to treat-but new therapies are improving outcomes.

Do I need to take thyroid hormone forever?

Yes. If you’ve had a total thyroidectomy, your body can no longer produce thyroid hormone. You’ll need to take levothyroxine daily for life. Even after a lobectomy, some people end up needing hormone replacement if the remaining lobe doesn’t produce enough. Regular blood tests to check TSH levels help your doctor adjust your dose.

Can radioactive iodine cause cancer?

There’s a small increased risk of developing other cancers later in life, especially if you receive high doses of radioactive iodine multiple times. Studies show a slight rise in leukemia and salivary gland cancer, but the absolute risk is low-less than 1% over 20 years. For most patients, the benefit of preventing thyroid cancer recurrence far outweighs this small risk.

Why do I feel so tired after thyroid surgery?

Fatigue after thyroid surgery is common. It can come from the surgery itself, thyroid hormone withdrawal before radioactive iodine, or your body adjusting to hormone replacement. Many patients describe brain fog, low energy, and mood swings-even when lab results look normal. Finding the right levothyroxine dose can take months. Some people benefit from adding T3 (liothyronine), though that’s not standard for everyone.

Can I have children after thyroid cancer treatment?

Yes. Most women can have healthy pregnancies after thyroid cancer treatment. It’s important to stabilize your thyroid hormone levels before conceiving, since low thyroid hormone can affect fetal development. Men don’t have fertility issues from radioactive iodine at standard doses. Doctors usually recommend waiting 6 to 12 months after RAI before trying to conceive to ensure radiation has cleared and hormone levels are stable.

Shivam Goel

Okay, but let’s be real-RAI isn’t just a pill, it’s a full-on exile. I had to sleep in the guest room for 5 days, no hugging my kid, no sharing a fork, and my dog looked at me like I was radioactive (which, technically, I was). The worst part? The taste. Everything tasted like metal and regret. And don’t even get me started on the low-iodine diet-no cheese? No bread? I felt like I was on a cult retreat.