The Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t just change how generic drugs get approved in the U.S.-it rewrote the rules of the entire pharmaceutical market. Before 1984, bringing a generic drug to market was nearly impossible. Brand-name companies held tight control over their patents, and generic makers couldn’t even test their versions until the patent expired. That meant patients paid more, and innovation stalled. The Hatch-Waxman Act fixed that-by creating a legal bridge between innovation and affordability.

What the Hatch-Waxman Act Actually Did

Passed in 1984, the full name is the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act. It’s called Hatch-Waxman because it was co-sponsored by Senator Orrin Hatch and Representative Henry Waxman. The goal? Balance two competing needs: give drug makers enough time to profit from their inventions, while letting generics enter the market quickly after patents expire. Before this law, generic companies had to run full clinical trials to prove their drugs worked-just like the original brand. That cost millions and took years. Hatch-Waxman changed that by creating the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). Instead of redoing safety and effectiveness studies, generic makers only had to show their version was bioequivalent-meaning it released the same amount of medicine into the body at the same rate as the brand. This cut development costs by about 75%. But there was a problem. The 1984 Supreme Court case Roche v. Bolar had ruled that even testing a drug during its patent term was illegal. Hatch-Waxman fixed that with something called the “safe harbor” provision. Now, generic companies can legally make, test, and study patented drugs before the patent runs out-just to gather data for FDA approval. That’s why most generic applications are filed years before the patent expires.How Generic Companies Get a Head Start

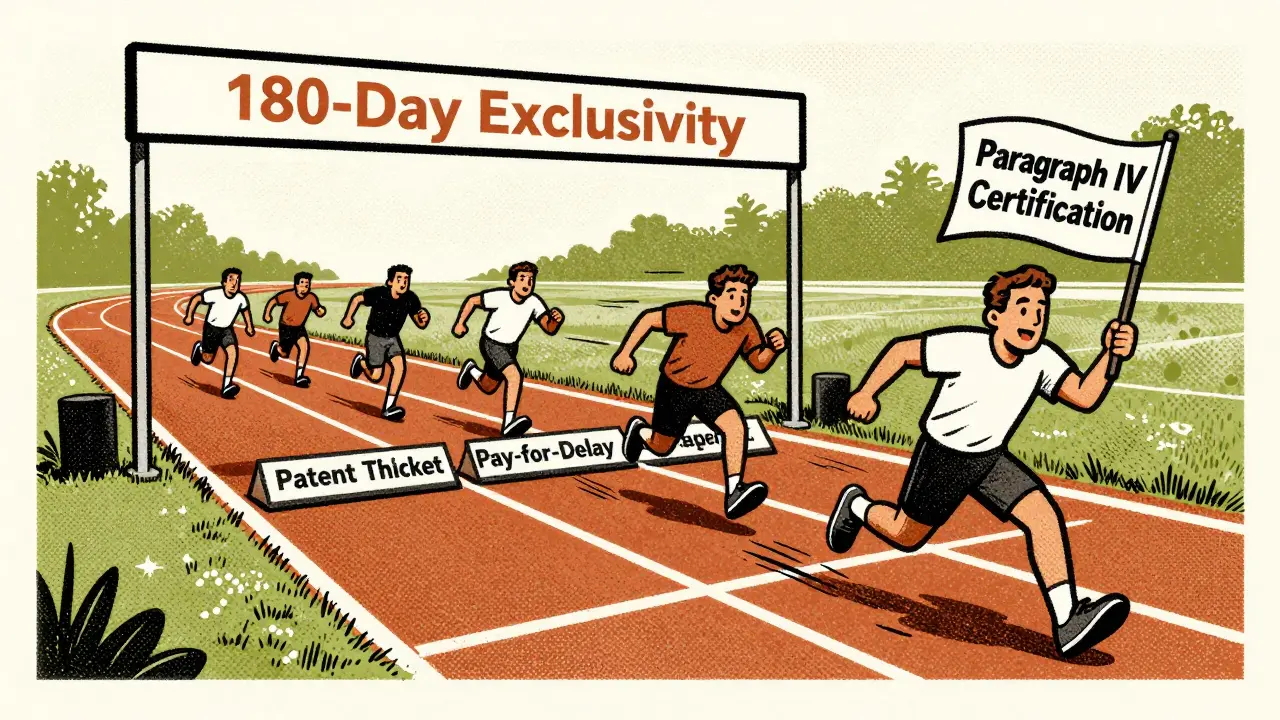

One of the most powerful tools in the Act is the Paragraph IV certification. When a generic company files an ANDA, it can say, “This patent is invalid or we won’t break it.” That’s a direct challenge. The brand-name company then has 45 days to sue. If they do, the FDA can’t approve the generic for 30 months-or until a court rules otherwise. This sounds like a delay, but it’s actually a strategic advantage. The first generic company to file a Paragraph IV challenge gets 180 days of exclusive market rights. No other generics can enter during that time. That’s huge. One company can make all the profit while others wait. That’s why, in the late 1990s, generic companies would camp outside FDA offices just to be first to file. The FDA changed the rules in 2003 to allow multiple companies to share that 180-day window if they filed on the same day. That reduced the “race to the courthouse” but didn’t eliminate the incentive. Today, the first filer still gets a massive edge-especially for blockbuster drugs.

How Brand Companies Got More Time

The Act didn’t just help generics. It also gave brand-name companies something they desperately wanted: patent term restoration. Developing a new drug takes years. On average, 6-7 of the 20-year patent life are spent in FDA review. That leaves little time to make a profit. Hatch-Waxman lets companies apply to extend their patent by up to 5 years-but only for time lost during regulatory review, and capped at 14 years total from the original approval date. The average extension granted? Just 2.6 years. But here’s the twist: companies didn’t stop there. They started filing dozens of secondary patents-on things like pill coatings, dosing schedules, or delivery methods. In 1984, the average drug had 3.5 patents. By 2016, it was 2.7 patents per drug. Today, some drugs have over 14 patents. This creates what experts call “patent thickets”-a maze of overlapping protections that make it hard for generics to enter, even after the main patent expires. Some brand companies also use “product hopping”-slightly changing a drug (like switching from a pill to a liquid) and pushing patients to the new version. Then they file a new patent on the change, resetting the clock. The FTC has flagged over 260 such cases between 2010 and 2022, mostly in cancer, autoimmune, and neurological drugs.The Hidden Costs of the System

The Hatch-Waxman Act saved U.S. consumers over $1.18 trillion between 1991 and 2011. Generic drugs now make up 90% of prescriptions but only 18% of total drug spending. That’s a massive win. But the system has been gamed. One of the biggest abuses is “pay-for-delay.” A brand company pays a generic maker to delay launching its cheaper version. Between 2005 and 2012, 10% of all generic challenges ended this way. In one case, a brand company paid $1.2 billion to delay a generic for a heart drug for over a year. That’s not competition-it’s collusion. Legal costs are also skyrocketing. A single Paragraph IV challenge can cost $15-30 million. Generic companies now need teams of 15-20 people just to manage patent filings and litigation. Meanwhile, brand companies spend millions more to defend their patents. The FDA’s Orange Book-a public list of patents linked to approved drugs-is often outdated or misleading. In 2022, 22% of patent disputes centered on whether a patent should even be listed there.

What’s Changing Now?

The system is under pressure. In 2022, Congress passed the CREATES Act, which forces brand companies to provide sample drugs to generics so they can test them. Before, some companies refused to sell samples, effectively blocking generic development. In 2023, the House passed the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act, which would ban pay-for-delay deals. It’s now in the Senate. If it becomes law, it could cut generic delays by months or even years. The FDA is also tightening the rules. Its 2022 draft guidance says patents on minor changes shouldn’t be listed in the Orange Book. And under the new GDUFA IV agreement, FDA review times for ANDAs are dropping from 10 months to 8 months by 2025. That’s faster than ever. Still, critics warn that too much reform could hurt innovation. Japan cut its patent protections in 2018 and saw a 34% drop in new small-molecule drugs. The U.S. can’t afford to go that far.Why It Still Works-Despite the Flaws

The Hatch-Waxman Act isn’t perfect. But it’s the reason 15,678 generic drugs are on the market today. It’s why your $500 brand-name pill is now a $15 generic. It’s why the U.S. gets generics to market 1.8 years faster than Europe. The core idea-that innovation and competition can coexist-is still valid. The problem isn’t the law. It’s how companies twist it. Patent thickets, pay-for-delay, product hopping-these aren’t features of Hatch-Waxman. They’re loopholes. The real test now is whether regulators and lawmakers can fix the abuse without breaking the system. Because if they do, the next decade could see even more savings, faster access, and better health outcomes for millions.What is the Hatch-Waxman Act?

The Hatch-Waxman Act, officially the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, is a U.S. law that created the modern system for approving generic drugs. It lets generic manufacturers prove their drugs are bioequivalent to brand-name drugs using an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), while also giving brand companies extra patent time to make up for delays in FDA approval.

How does the ANDA pathway work?

The ANDA pathway allows generic drug makers to skip full clinical trials. Instead, they must prove their product is bioequivalent to the brand-name drug-meaning it delivers the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate. This reduces development time and cost by about 75% compared to a new drug application.

What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement by a generic drug applicant claiming that a patent listed for the brand-name drug is invalid or won’t be infringed. This triggers a 45-day window for the brand company to sue. If they do, FDA approval is automatically delayed for up to 30 months while the lawsuit plays out.

Why do generic companies get 180 days of exclusivity?

The first generic company to file an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification gets 180 days of exclusive marketing rights. This incentive encourages companies to challenge weak patents. Even though the FDA now allows multiple companies to share this window if they file on the same day, the first filer still holds a major financial advantage.

What are patent thickets and product hopping?

Patent thickets are when a brand company files dozens of secondary patents on minor changes-like a new coating or dosage form-to block generics. Product hopping is when a company slightly changes a drug (e.g., from pill to liquid) and pushes patients to the new version, then patents the change to reset the exclusivity clock. Both tactics delay generic entry and are under scrutiny by the FTC.

How has the Hatch-Waxman Act affected drug prices?

Generic drugs account for 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. but only 18% of total drug spending. When a generic enters the market, prices typically drop to 15% of the brand-name price within six months. Since 1991, the Act has saved the U.S. healthcare system over $1.18 trillion. However, abuse tactics like pay-for-delay have added $149 billion in extra costs since 2010.

Cheryl Griffith

This law literally saved my dad’s life. His insulin went from $400 to $15 because of generics. I never realized how broken the system was until I saw the difference firsthand.

Thank you for explaining this so clearly.