When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it will? The answer lies in two numbers: Cmax and AUC. These aren’t just technical terms-they’re the foundation of whether a generic drug gets approved and whether it’s safe and effective for you to take.

What Cmax and AUC Actually Measure

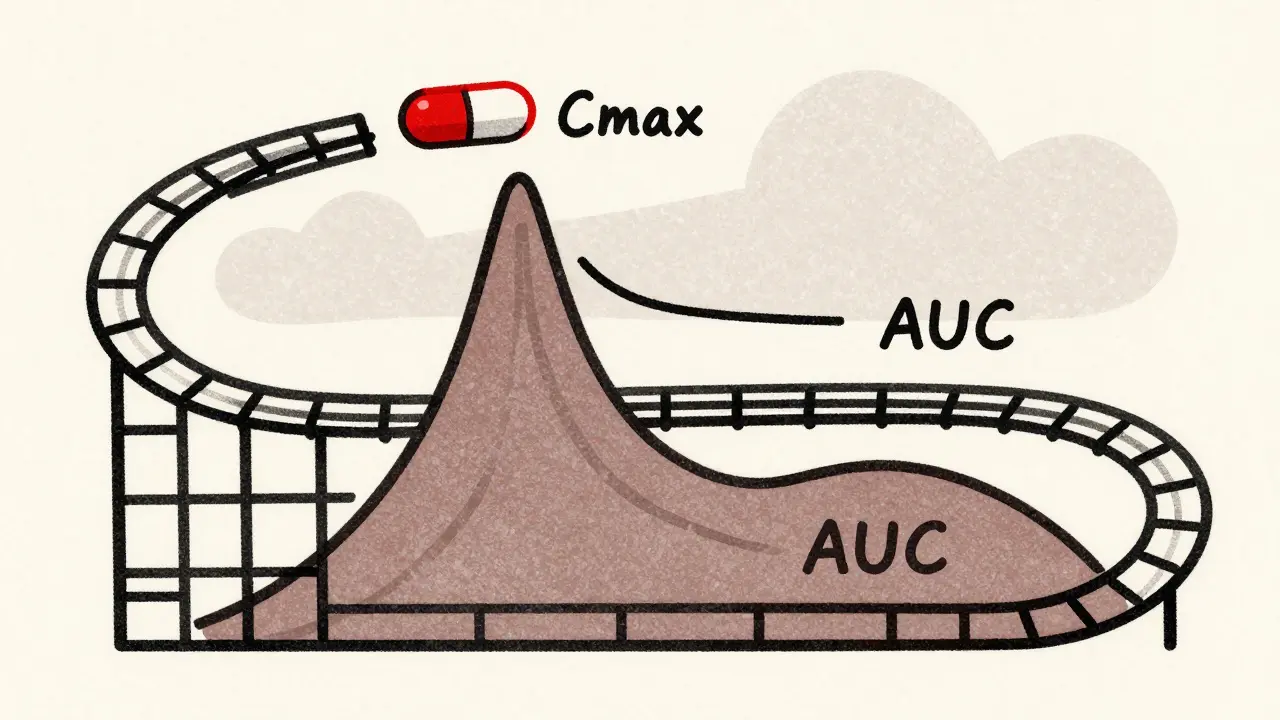

Cmax stands for maximum concentration. It tells you how high the drug goes in your blood after you swallow it. Think of it like the peak of a rollercoaster-the highest point before it drops. If a drug needs to hit a certain level quickly to relieve pain or stop a seizure, Cmax is what matters most.

AUC, or area under the curve, measures total exposure. It’s the entire area under the graph of drug concentration over time. Imagine tracing the shape of the rollercoaster track from start to finish. AUC tells you how much of the drug your body has absorbed over hours or days. For drugs that work slowly or need to stay in your system all day, like blood pressure meds, AUC is the key.

These aren’t guesses. They’re measured in real people. Volunteers take the drug, and blood samples are drawn every 30 minutes to two hours for up to 72 hours. Labs use ultra-sensitive machines-LC-MS/MS-that can detect as little as 0.1 nanograms per milliliter. That’s like finding a single grain of salt in an Olympic swimming pool.

Why Both Numbers Are Non-Negotiable

Regulators don’t just check one. They demand both Cmax and AUC pass the same strict test. Why? Because one can lie while the other tells the truth.

Imagine two pills: one releases the drug fast, giving you a high Cmax but then drops off quickly. Another releases slowly, with a lower peak but lasts longer. Both could have the same AUC-same total exposure-but very different Cmax. The first might cause side effects from the spike. The second might not work fast enough to stop a migraine.

That’s why the FDA and EMA require both to be within 80% to 125% of the brand-name drug’s values. This range isn’t random. It comes from decades of data showing that if the difference is smaller than 20%, the risk to patients is negligible for most drugs.

But here’s the catch: the numbers are never compared directly. They’re log-transformed first. Why? Because drug levels in blood don’t follow a straight line-they follow a curve that’s skewed. Logarithmic transformation turns that curve into a straight line, making the math accurate. Without this step, you’d get false results.

The 80%-125% Rule: Where It Came From and Why It Sticks

This rule didn’t come from a lab. It came from a meeting.

In 1991, scientists from the U.S., Europe, and Japan gathered in Boston to solve a problem: how to approve generics without endless clinical trials. They looked at thousands of drug studies and realized that if the ratio of generic to brand drug exposure stayed within 80%-125%, patients had no increased risk of side effects or reduced effectiveness. The math was solid. The logic was simple.

Since then, over 1,200 generic drugs have been approved in the U.S. alone each year-almost all based on this rule. The WHO confirms that 120+ countries use it. It’s the global standard.

But there are exceptions. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, lithium, or levothyroxine-small changes can be dangerous. The EMA now recommends tighter limits: 90%-111%. The FDA allows this too, but only if the drug shows high variability in how people absorb it. That’s why some generics for these drugs are harder to find-they’re harder to prove equivalent.

What Happens When Cmax or AUC Fails

It’s not rare. About 15% of bioequivalence studies fail-not because the drug is bad, but because of how they’re done.

The most common mistake? Not sampling early enough. If you only take blood samples at 1, 2, and 4 hours, you might miss the real Cmax. For fast-absorbing drugs like ibuprofen, the peak can happen at 45 minutes. If you don’t sample at 30 and 60 minutes, you’ll underestimate it. That’s enough to fail the 80%-125% test.

Another issue? Using nominal times instead of real ones. If a blood draw was supposed to be at 2 hours but happened at 2 hours and 15 minutes, you can’t just pretend it was on time. Regulators require actual sampling times to be used in calculations. Many small labs still get this wrong.

When a study fails, the company has to redesign it. More volunteers. More blood draws. More time. More cost. That’s why some generics take years to launch-and why some never make it to market.

How This Affects You as a Patient

You might wonder: if two drugs have the same AUC and Cmax, why do some people say generics don’t work as well?

Here’s the truth: for 95% of people, they do. A 2019 analysis of 42 studies in JAMA Internal Medicine found no meaningful difference in outcomes between brand and generic drugs that met bioequivalence standards. That includes heart meds, antidepressants, and seizure drugs.

But if you’ve ever switched from one generic to another and felt different-like your blood pressure spiked or your pain returned-that’s likely not because of bioequivalence failure. It’s because different generics use different fillers, coatings, or release mechanisms. Those don’t affect Cmax or AUC, but they can change how the pill feels in your stomach or how fast it dissolves.

That’s why doctors sometimes stick with one brand or generic. Not because of safety, but because consistency matters. If you’re stable on one version, switching might cause anxiety-even if the science says it’s fine.

What’s Changing in the Future

Regulators are starting to look beyond Cmax and AUC-for certain drugs.

Modified-release pills, like those that release medication over 12 hours, can have multiple absorption peaks. One AUC number doesn’t capture that. The FDA now suggests looking at partial AUC-for example, the exposure in the first 4 hours-to better match how the drug works.

For highly variable drugs, like some antibiotics or epilepsy meds, regulators are using scaled bioequivalence. Instead of a fixed 80%-125%, the range widens based on how much the drug varies between people. This keeps good drugs from being blocked just because they’re unpredictable.

And soon, computer modeling might replace some human studies. If a drug’s behavior is well understood, regulators might accept simulations instead of 24 volunteers taking blood draws for days. But even then, Cmax and AUC will still be the baseline.

As Dr. Robert Lionberger of the FDA said in 2022: "AUC and Cmax will remain the primary bioequivalence endpoints for conventional drug products for the foreseeable future." Why? Because they’ve been tested, proven, and trusted for over 40 years. No other metric comes close.

Final Takeaway: Trust the Numbers, But Know the Limits

Cmax and AUC are not perfect. But they’re the best tools we have to ensure that a $5 generic pill works like a $50 brand-name one. They’re the reason you can save money without risking your health.

When you take a generic, you’re relying on thousands of blood samples, hundreds of volunteers, and decades of science-all boiled down to two numbers. And if those numbers pass the 80%-125% test, you can be confident: it’s the same drug. Just cheaper.

What does Cmax mean in bioequivalence?

Cmax stands for maximum plasma concentration-the highest level a drug reaches in your bloodstream after taking it. It tells you how fast the drug is absorbed. For drugs that need to work quickly, like painkillers or seizure meds, Cmax is critical because too high a peak can cause side effects, and too low a peak means it won’t work.

What is AUC in bioequivalence testing?

AUC, or area under the curve, measures total drug exposure over time. It’s calculated by plotting drug concentration in the blood against time and measuring the space under that curve. AUC tells you how much of the drug your body has absorbed overall. For drugs that need to stay active for hours, like blood pressure or antidepressant meds, AUC is the key indicator of effectiveness.

Why do regulators require both Cmax and AUC?

Because they measure different things. Cmax tells you about the speed of absorption; AUC tells you about the total amount absorbed. A drug could have the same total exposure (AUC) as the brand but absorb too fast (high Cmax), causing side effects-or too slow (low Cmax), failing to work. Both must meet the same 80%-125% range to ensure safety and effectiveness.

What is the 80%-125% rule in bioequivalence?

The 80%-125% rule means the ratio of the generic drug’s Cmax and AUC compared to the brand-name drug must fall between 80% and 125%. This range is based on decades of clinical data showing that differences smaller than 20% don’t affect safety or effectiveness for most drugs. The numbers are log-transformed before analysis because drug levels follow a skewed, not normal, distribution.

Are there exceptions to the 80%-125% rule?

Yes. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, lithium, or levothyroxine-small changes can be dangerous. The EMA and FDA allow tighter limits of 90%-111% for these. Also, for drugs with high variability between patients, regulators may use scaled bioequivalence, which adjusts the range based on how much the drug varies from person to person.

Why do some people feel different when switching to a generic?

If the generic meets bioequivalence standards, the difference isn’t due to Cmax or AUC. It’s likely from inactive ingredients-fillers, coatings, or binders-that affect how the pill dissolves or how it feels in your stomach. These don’t change drug absorption but can cause minor differences in side effects or perception. If you notice a change, talk to your doctor. Sticking with one version is often safer than switching back and forth.

Do bioequivalence studies always use human volunteers?

For most conventional drugs, yes. Studies typically involve 24-36 healthy volunteers in a crossover design, where each person takes both the brand and generic drug at different times. Blood samples are drawn frequently over 24-72 hours. However, for some complex drugs, regulators are exploring computer modeling to reduce the need for human testing-but Cmax and AUC remain the required endpoints.

Sidhanth SY

Been taking generics for years and never had an issue. Honestly, the science behind Cmax and AUC is way more solid than most people think. I work in pharma logistics and see how strict these tests are. If it passes, it works. No magic, no conspiracy.